Friday, May 14 through Monday, May 17

Paula: After flying from Cusco to Lima, we spent the past several days near the southern coast of Peru in the town of Ica. Ica is four hours by bus from Lima, a coastal drive that was shrouded in mist and fog with large sand dunes on either side of the road. The western lowlands of Peru are comprised mostly of desert with numerous oases that sit along the river basins draining the Amazon into the Pacific Ocean.

We decided to spend a few days relaxing in a small resort that is geared toward families. This was actually a much-needed break before we begin our marathon trip to Africa. Many people also use Ica as a stopping off point to see the Nazca Lines but we decided to pass on this adventure which requires a flight in a small plane (4 seats). The lines are large carvings of animals placed by pre-Columbian tribes a thousand years ago. They can only be appreciated by plane and we have heard that the flights are not tolerated well by those with a weak stomach. That disqualified David and me - actually I think we were all content to have a few "down days," and we jointly decided that we could miss this one sight, given all we have seen so far (especially with the anxieties that at least some of us were feeling).

Las

Dunas ("the dunes") is a resort that sits among huge sand dunes

and features dune buggy rides and sand surfing. We tried a little of both

and especially enjoyed our buggy adventure through the sand dunes that were

just spectacular. The dunes reminded us of the Thar Desert in India, but here

they were much larger and seemed to go on forever. The ride was actually thrilling

as the drivers would take us up to the

Las

Dunas ("the dunes") is a resort that sits among huge sand dunes

and features dune buggy rides and sand surfing. We tried a little of both

and especially enjoyed our buggy adventure through the sand dunes that were

just spectacular. The dunes reminded us of the Thar Desert in India, but here

they were much larger and seemed to go on forever. The ride was actually thrilling

as the drivers would take us up to the top of the dunes and then race steeply down. We sped up and down steep inclines

and around large potholes. It was basically a roller-coaster ride on sand.

top of the dunes and then race steeply down. We sped up and down steep inclines

and around large potholes. It was basically a roller-coaster ride on sand.

We

were also given the opportunity to surf on small boards (similar to a snowboard)

down one of the dunes. After parking the buggies on the ridge of a particularly

high dune and waxing the sand boards, our drivers (who spoke no English) sat

us on the boards and without any instruction got ready to simply give us a

We

were also given the opportunity to surf on small boards (similar to a snowboard)

down one of the dunes. After parking the buggies on the ridge of a particularly

high dune and waxing the sand boards, our drivers (who spoke no English) sat

us on the boards and without any instruction got ready to simply give us a

push. David and Katie attempted to question them in Spanish but they just

shrugged and pointed to the boards. David was the lucky one - he received

the first push and we all watched him quickly disappear down the dune, shocked

at how fast he made it to the bottom. When he finally stopped, he fell over

and didn't move. Fortunately, he had collapsed from the exhilaration and after

giving us the thumbs up, the rest of us were on our way too.

push. David and Katie attempted to question them in Spanish but they just

shrugged and pointed to the boards. David was the lucky one - he received

the first push and we all watched him quickly disappear down the dune, shocked

at how fast he made it to the bottom. When he finally stopped, he fell over

and didn't move. Fortunately, he had collapsed from the exhilaration and after

giving us the thumbs up, the rest of us were on our way too.

The

resort actually reminds us a little of Club Med. It was school vacation week

in Peru so there were many young families participating in all the activities

available. As far as we could tell, we were the only Americans. Meals were

served buffet style and after-dinner shows included a kid's talent show complete

with Barney and Sponge Bob. We all got a kick out of hearing the various kids'

songs in Spanish. We also noticed that "Happy Birthday" is always

sung first in English and then in Spanish - we have no clue why.

The

resort actually reminds us a little of Club Med. It was school vacation week

in Peru so there were many young families participating in all the activities

available. As far as we could tell, we were the only Americans. Meals were

served buffet style and after-dinner shows included a kid's talent show complete

with Barney and Sponge Bob. We all got a kick out of hearing the various kids'

songs in Spanish. We also noticed that "Happy Birthday" is always

sung first in English and then in Spanish - we have no clue why.

Sunday was David's 15th birthday and in addition to a surprise cake at lunchtime,

we purchased tickets to a football (soccer) match between Allianz-Lima and

Colonel- Bolognese.

The Lima team is considered the best team in Peru and we were excited to finally

have a chance to see a professional football game outside of the USA.

Bolognese.

The Lima team is considered the best team in Peru and we were excited to finally

have a chance to see a professional football game outside of the USA.

The game was played in the Ica Stadium which seats about 5,000 fans. We were

advised to arrive an hour before the game in order to secure good seats (seating

was unreserved). Even then, the stadium was well over half-full when we arrived.

We found good seats at mid-field among a relatively tame group of spectators,

and ended up being treated to a fast moving game with an unusually high score

(6-2,

Allianz-Lima). The game was rough and included numerous injuries, three penalty

kicks and one ejection. A loud and boisterous group at the end of field chanted,

banged on drums and blew their horns non-stop. We have seen this before on

television, but had no idea that it went on for literally the

(6-2,

Allianz-Lima). The game was rough and included numerous injuries, three penalty

kicks and one ejection. A loud and boisterous group at the end of field chanted,

banged on drums and blew their horns non-stop. We have seen this before on

television, but had no idea that it went on for literally the  entire

game! Police dressed in riot gear protected the field and there was also a

barbed wire fence between the stands and field - we assume that is simply

standard security here.

entire

game! Police dressed in riot gear protected the field and there was also a

barbed wire fence between the stands and field - we assume that is simply

standard security here.

Monday

we headed back by bus to Lima where we spent the night in preparation for

tomorrow's flight to Miami and Atlanta. From Atlanta we have a 16-hour flight

to Johannesburg, followed by two more flights until we reach Arusha, our final

destination in Tanzania.

Monday

we headed back by bus to Lima where we spent the night in preparation for

tomorrow's flight to Miami and Atlanta. From Atlanta we have a 16-hour flight

to Johannesburg, followed by two more flights until we reach Arusha, our final

destination in Tanzania.

Tomorrow will be the closest we have been to home in over 4 months. Some good ole American cooking (even at the Atlanta Airport Marriott) sounds perfect about now.

Katie's Kwick Kwacks: The Effects of Inca Culture on Peruvian Life Today. During our time in Peru, we have constantly taken note of the many effects Inca culture has had on the people living here today. We have seen this all through the countryside, and are amazed by how strong of an influence it is. The Peruvian peoples' customs, traditions, and ways of life are very similar to how they were 500 years ago. We therefore had the opportunity to experience what I like to call, "living history." The following bullets list some of the ways the Incas have impacted Peruvian life today.

-Ceremonies and rituals (offerings to mother earth, ceremonies at the beginning of the harvest, respect for ancestors-earth oven and chicha rituals-festivals, songs and dance)

-Farming Tools and Methods (plows, hoes and lampas-men dig up crop and women pick them up in bundles-some people work on large plots of land owned by a landlord and others have small farms just for their families)

-Weaving

Tools and Methods (women use alpaca and llama fibers with Inca geometric patterns-they

use Inca tools such as traditional spinners and looms, animal bones, natural

dyes, etc.-they spin whenever they have time such as when watching animals-they

sell some of their products in the market)

-Weaving

Tools and Methods (women use alpaca and llama fibers with Inca geometric patterns-they

use Inca tools such as traditional spinners and looms, animal bones, natural

dyes, etc.-they spin whenever they have time such as when watching animals-they

sell some of their products in the market)

-Clothing (traditional dress for men and women--blankets for carrying babies)

-Food and drink (coca leaves for offerings and chewing, chicha all day long, potatoes for every meal, guinea pig as a delicacy)

-Language (they still speak Quechua and practice some traditions for certain greetings)

-Homes (similar style made of stone, thatched roof and dirt floors-no furniture inside, small fire with guinea pigs running around-Inca pots)

-Raising

live stock (llamas, alpacas, etc.)

-Raising

live stock (llamas, alpacas, etc.)

-Jobs and roles in family (both men and women work in the fields-women take care of the kids and carry them on their backs-men do heavy labor with plowing while women weave and watch animals-children work at an early age)

-Trading (many people don't really use money-they trade people for things from different areas and villages, such as fruit from the jungle and potatoes from the highlands)

At first glance, it may seem that the Inca civilization was an untold mystery-compared

to many civilizations, there are few places where artifacts and ruins can

still be seen. The Incas had no written language to record their customs,

history and beliefs. We have few written sources to reveal this information.

They were taken over by a group of greedy Europeans. These people destroyed

their civilization and all of its wealth and power.

Despite all of this disaster, however, there is still a tremendous amount of life. The Inca civilization was one of the shortest we have learned about on the entire trip, yet, its influence is one of the strongest. Their heritage is told through the people. The Inca traditions, customs, and ways of life are still well preserved in Peruvian culture today. The people do all of the things I described in this essay. It isn't for the tourists, nor is it something they personally decide to follow. All of their ancestors have done it that way--why should they do any different? They don't seem to want a change. This is the true meaning of a lasting culture.

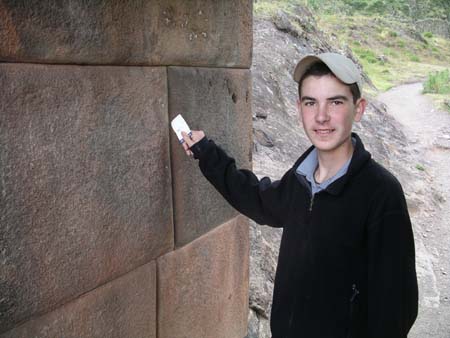

David's Daily Dump: My Theory on Inca Construction. As our exploration

of Peru unraveled, I couldn't help but notice the unique and staggering architecture

of the unbelievable Incan empire. One of the things that I took particular

interest in were the walls, which were composed of many unique stones, each

with a different size and shape. Each rock seemed to be totally different

from one another, yet they all fit together like the pieces of a puzzle. Some

of the stones were very odd, and had many curves, indents, and bends. Despite

the unusual shapes of these bizarre and random rocks, the surrounding stones

matched every single arc, and fit in without a flaw. I couldn't understand

why they didn't just carve all the stones into one common shape and size.

Not only would this save work, but also time, and the sweat and blood of hundreds.

It didn't make sense to me. It is much harder to carve rocks according to

another's shape, rather than to just carve them into a set design. After much

time and thought, I created my own hypothesis...

My

theory is that the Incas built their buildings and cities with giant stones,

which were cut into smaller pieces for easier transportation. When I see a

section of an Inca building made up of weirdly shaped rocks, I picture them

all together as one…one big rock. I believe that when the Incas broke

their huge rocks (even if they tried to plan the way they would

My

theory is that the Incas built their buildings and cities with giant stones,

which were cut into smaller pieces for easier transportation. When I see a

section of an Inca building made up of weirdly shaped rocks, I picture them

all together as one…one big rock. I believe that when the Incas broke

their huge rocks (even if they tried to plan the way they would  crack),

the direction in which they split was random and inconsistent. When you throw

a rock against another hard surface, the way that it breaks is totally unpredictable.

Whether a stone splits into a few or many pieces, no matter the shape, the

pieces can still be put back together. Even if a stone had a hundred curves

and bends, the other pieces would match it perfectly. With a little polishing,

reconstructing, and transportation, a big rock in the quarry would be part

of a whole new wall, but in many different shaped pieces.

crack),

the direction in which they split was random and inconsistent. When you throw

a rock against another hard surface, the way that it breaks is totally unpredictable.

Whether a stone splits into a few or many pieces, no matter the shape, the

pieces can still be put back together. Even if a stone had a hundred curves

and bends, the other pieces would match it perfectly. With a little polishing,

reconstructing, and transportation, a big rock in the quarry would be part

of a whole new wall, but in many different shaped pieces.

First I should talk about how the Incas "carved" or cut their rocks.

The method is still debated upon, but I will describe one of the theories.

One idea was that the Incas inserted pieces of wet woo d

into small notches that they carved into huge stones. They would add water

and then wait until the wood froze, and expanded. The expansion would cause

the rock to split, and create a separate, smaller piece of stone. Although

the notches were placed in a straight line so that the rock would split evenly,

it didn't always come out perfectly. This theory was tested by archeologists,

and it worked, but not always exactly the way they planned. But it didn't

matter if the rocks turned out uneven, because the separate stone would still

fit the side of the original rock which it broke off of. Once another piece

of the same big rock was detached, the two new pieces would match precisely,

and no additional carving would be needed (except for polishing the edges).

d

into small notches that they carved into huge stones. They would add water

and then wait until the wood froze, and expanded. The expansion would cause

the rock to split, and create a separate, smaller piece of stone. Although

the notches were placed in a straight line so that the rock would split evenly,

it didn't always come out perfectly. This theory was tested by archeologists,

and it worked, but not always exactly the way they planned. But it didn't

matter if the rocks turned out uneven, because the separate stone would still

fit the side of the original rock which it broke off of. Once another piece

of the same big rock was detached, the two new pieces would match precisely,

and no additional carving would be needed (except for polishing the edges).

I also think it's possible that the Incas didn't plan the way the rocks were

going to be shaped. Maybe they rolled massive rocks down mountains, or dropped

stones onto other rocks, or simply hammered away not caring how they split.

I think that this may be true because no matter how the rocks broke, all the

pieces could still be put back together, and would fit in perfectly with one

another.

Now you may ask, "If the Incas were using huge rocks to build their walls, why did they take the time to break them into smaller ones when they could have used the big rocks in their original forms?" There are two answers to this question. First, the quarries where the Incas got their rocks were sometimes miles away from the building sites! The smaller stones were much easier to transport than the humongous ones. Second, the huge rocks which the Incas found sometimes weighed more than 300 tons, and were virtually impossible to budge! Obviously, the smaller stones would be easier to carry.

Another thing that I noticed (especially at Machu Picchu) was that some

buildings (usually with great importance) were made up of all rectangular

stones. When I first observed a temple with this type of construction, I realized

that it totally threw off my hypothesis. I thought about it for a while, and

then came up with an answer. Chances are that when the Incas found a quarry,

they found many different sized stones. Some small, some big, some huge, and

some gargantuan! When they found big stones they  probably

used the method that I have already described, but what did they do with the

small ones? They had no clue which stone was part of which rock. I think that

they carved these rocks into a common shape (in this case a rectangle) and

used all the small rocks they found to build an important structure. Other

people think that it was just the architect's personal style, or a type of

architecture reserved for the most essential buildings of the empire…who

knows?

probably

used the method that I have already described, but what did they do with the

small ones? They had no clue which stone was part of which rock. I think that

they carved these rocks into a common shape (in this case a rectangle) and

used all the small rocks they found to build an important structure. Other

people think that it was just the architect's personal style, or a type of

architecture reserved for the most essential buildings of the empire…who

knows?

It's been really neat writing this essay and explaining my own hypothesis about the Incas. Whether my theory is correct or incorrect I do not know. Whether my idea has already been thought of or recognized as a possibility I also don't know. But it doesn't really matter to me. I formed my hypothesis on my own, and supported it. In fact, I have also seen evidence that rejects my thoughts. We found huge stones, weighing over 100 tons, at a site outside Cusco, which were carried for two miles by the Incas. Why didn't they just cut them into smaller pieces? This is just another of the many mysteries of the Inca empire, which left no written records.